On December 2nd 2021, the U.S. Transportation Security Administration (TSA) made “enhancing cybersecurity” their 2022 new year’s resolution. The TSA did this by releasing two new mandatory security directives targeting “higher risk” freight and passenger railroad carriers and rail transit operations. They accompanied the security directives with a non-mandatory Information Circular that would hopefully inspire lower risk (non-ferry) surface transportation operations – namely over-the-road bus (OTRB) and freight and passenger rail agencies not covered in the security directives – to voluntarily strengthen their cybersecurity programs.

While applicability differs with each document, the required actions or recommended measures are the same:

- Designate corporate-level primary and alternate cybersecurity coordinators to facilitate communication with the TSA and CISA and work with law enforcement and emergency response agencies. The cybersecurity coordinators must be U.S. citizens who are security clearance-eligible and accessible 24/7.

- Report cybersecurity incidents to CISA within 24 hours after the incident is identified.

- Implement a cybersecurity incident response plan that includes “measures to reduce the risk of operational disruption, or other significant business or functional degradation” in the event of a cybersecurity incident.

- Complete a cybersecurity vulnerability assessment that identifies cybersecurity gaps and remediation measures to address them.

Besides Amtrak, the passenger rail transit agencies required to comply with TSA Security Directive 1582-21-01 are those included in Appendix A of Part 1582 of Title 49 of the Federal Code of Regulations. Oddly, only half of the “systems” listed in Appendix A are rail agencies as the other half are bus and/or ferry operators. Besides ferries being expressly excluded from Part 1582’s scope, the inclusion of OTRB seems out of place as Part 1584 addressing the same security training requirements for OTRB doesn’t use 1582’s Appendix A, but rather has its own county-based Appendix A. After scrubbing bus and rail operators, the table below represents the 23 non-Amtrak passenger rail transit agencies required to follow the TSA Security Directive along with their annual rail ridership.

These 23 passenger rail agencies legally obligated to comply with the security directives started the new year by working to achieve the deadlines of completing a vulnerability assessment by March 31, 2022 and implementing an incident response plan by June 29, 2022. However, those agencies who received these measures merely as non-mandatory recommendations through the Information Circular are encouraged to do them “as soon as practicable”. The passenger rail transit agencies that fall in this category, in particular, may benefit from considering the following questions:

- What methodology was used to identify “higher risk” passenger rail transit agencies?

- Is our transit agency truly at lower risk or was it a mistake we weren’t included?

In the footnotes of supporting documentation justifying the security directives, the TSA provided this insight into the methodology used to identify “higher risk” passenger rail transit agencies for which the directives would be mandatory:

Risk ranking is based on considerations related to ridership, location of services provided (use of the same stations and stops), and relationship between feeder and primary systems.

Note that, at least publicly, risk determinations did not address the threat environment in which passenger rail transit agencies exist. Rather – based on significant ridership disparities among those included – risk seems to have been primarily influenced by urban popular centers and therefore includes much smaller agencies as a result of their geographical association with larger ones. The table below includes passenger rail transit agencies that did not make the list despite having more than 12 times the ridership of the smallest agencies that did make the list. It is noteworthy that San Diego, Dallas, and Houston are urban areas that were included in Part 1584‘s Appendix A outlining OTRB applicability. Similarly, all of them (as well as others) are included in Part 1580‘s high threat urban areas.

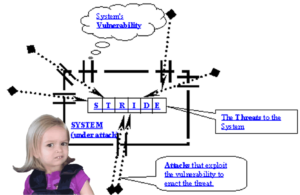

Recall that cyber risk is a function of threat agents, the vulnerabilities they explain, and the impact of the realized threat event. The TSA is absolutely correct in the need for enhanced cybersecurity “due to the ongoing cybersecurity threat to surface transportation system and associated infrastructure”. Based on their own explanation of risk ranking, the validity of the TSA’s determination of “higher risk” passenger rail systems is only as strong as the apparent assumption that a given threat is targeting small and large passenger rail systems alike to disrupt the entirety of one of the eight urban areas selected. In light of the prevalence of ransomware attacks targeting United States critical infrastructure, non-mandatory passenger rail transit agencies would be wise to avoid false confidence based on the TSA’s seemingly narrow threat assumptions.